DISCONNECTED?

“Social time keeps us healthy in the city”

The city is a loud and hectic place, while in the countryside long distances make everyday life harder. Mazda Adli, psychiatrist and stress researcher, explains how the two environments can benefit from each other.

Interview: Judy Born

Illustrations: Emmanuel Polanco

DISCONNECTED?

“Social time keeps us healthy in the city”

The city is a loud and hectic place, while in the countryside long distances make everyday life harder. Mazda Adli, psychiatrist and stress researcher, explains how the two environments can benefit from each other.

Interview: Judy Born

Illustrations: Emmanuel Polanco

Mr Adli, when people are talking about city vs. countryside, most of them refer to large cities. What is the threshold for a large city?

That threshold is surprisingly low: in Germany, any town with at least 100,000 inhabitants is defined as a “Großstadt” or large city. The country has only 4 cities with more than 1 million inhabitants; these are Berlin, Hamburg, Munich and, by the skin of its teeth, Cologne. However, we have quite a few urban areas consisting of several cities in close proximity, for example the Ruhrgebiet area and the Rhine-Main region.

Will our future be decided in the cities?

Yes. It most certainly will be. Cities have always been economic and academic, political and cultural centres. People are drawn to them; it is where atmospheres and trends develop and emanate from. Cities are the integration machinery of an open society. They are pressure cookers for the population's sensitivities. Which is why we better make sure cities are and will remain good places to live.

Does city life make us ill?

It might occasionally be stressful but while crowded roads and underground trains may be annoying, they don't necessarily make us ill. It only starts to affect our health when the stress of urban living turns into a permanent strain that overwhelms us, especially social stress.

What does that mean?

Social stress can seriously affect our mental health and is primarily triggered by two factors in the city: social isolation and social density. Social isolation means a feeling of not belonging or experiencing loneliness. Or it could mean social exclusion because you cannot sufficiently partake in what the city has to offer because of financial, physical or social barriers or because of discrimination. A feeling of belonging, on the other hand, is a vital protective element. It makes us resilient in the face of everything that is stressful about city life. As long as we can offset stress with social connectedness, we are fine.

What does “social density” mean?

It refers to feeling boxed in, when you don't have enough space. Social density becomes a stress factor when there is no possibility to escape the hustle and bustle of the city, for example in a room of your own or at least somewhere you can close the door behind you.

You and a few others founded the Interdisciplinary Forum Neurourbanism in Berlin. Your mission is to ensure that there will be cities worth living in for all of us in the future. How do you approach this goal?

We are a group of experts from different fields, such as city planning, architecture, psychiatry, philosophy, sociology, medicine and many others. Together, we examine the influence of living in the city on our emotions and our mental health. We explore these factors, make them measurable and study what impact they have on social interactions but also nature, the structure of cities and buildings.

Can you give us a concrete example of this work?

We have launched the citizen-scientific project “your emotional city” in Berlin. Everybody who would like to participate can download a free app that will follow them around the city for a week asking about emotional experiences in different social contexts. This way, we learn when and where people feel safe or insecure, happy or sad, tense or relaxed. The project will go on for several years, and our hope is that over time we will get some sort of emotional weather map of Berlin. The German capital is just the start and is planned to be followed by additional cities such as Melbourne, Beirut or Santiago de Chile. Everybody who would like to contribute to this project will find more information at futurium.de/de/ deine-emotionale-stadt.

Mazda Adli is chief physician at Fliedner Klinik in Berlin and head of the research unit for “affective disorders” at the Charité’s Department of Psychiatry and Neurosciences. In addition, he is a stress researcher, university professor and writer. His book “Stress and the City: Warum Städte uns krank machen. Und warum sie trotzdem gut für uns sind” was published in 2017.

Mazda Adli is chief physician at Fliedner Klinik in Berlin and head of the research unit for “affective disorders” at the Charité’s Department of Psychiatry and Neurosciences. In addition, he is a stress researcher, university professor and writer. His book “Stress and the City: Warum Städte uns krank machen. Und warum sie trotzdem gut für uns sind” was published in 2017.

When are cities good for us?

When we use everything available to us to counter the negative aspects, especially social isolation. That includes parks, public spaces, cultural offers. Theatres, for instance, also have a health mandate, if you ask me. They are meeting places fostering interactions, enabling us to get in touch with others. The rule of thumb is: time we spend outside our home is better for our psyche than time we spend within, because it is usually social time which keeps us healthy in the city.

Isn't country life healthier in general, though?

No, it can be stressful in a different way. Organising everyday life is more taxing because distances are longer, the educational and cultural offer is less varied or there is not enough or not the right kind of medical care. Also, we know that people living in the countryside are more likely to be affected by obesity and eat less healthily. Studies have shown that commuters engage less in social activities: 10 percent less per every 10 minutes of commuting time. At the same time, mental problems are on the rise.

But life in the countryside isn't as anonymous as in the city.

Traditionally, it may have been the case that social bonds are stronger and people are looking out for each other more. But that doesn't necessarily go for newcomers. Being accepted in the community can be quite difficult. And instead of the big city's anonymity you have to deal with social control which may take some getting used to.

Well, we are not all alike: while the city isn't for everyone, not everybody fancies living in the countryside either.

There are pros and cons to both urban and rural living. We need to be careful not to focus exclusively on the disadvantages of both options. I think, the benefits of urban life should be offered in rural environments, too, and vice versa. That would be an ideal compromise. After all, let's be realistic: Most people don't have the luxury of choosing where to live based on their personal preferences and needs. You have to be able to afford this, too. More often than not, the financial background, family, children and job determine where people live.

If you could choose between a country estate with all the trimmings and a small apartment in the city, what would it be?

I am an urbanite through and through; I would always choose the apartment in the city.

Judy Born works as a freelance journalist and loves big cities. Born in Stockholm she has already lived and worked in Munich, London and Berlin. Currently she lives in Hamburg.

Judy Born works as a freelance journalist and loves big cities. Born in Stockholm she has already lived and worked in Munich, London and Berlin. Currently she lives in Hamburg.

Also interesting

Karl-Heinz Paqué // Cities are booming while the countryside is dying?

Germany boasts an enviable variety of economic centres in both urban and rural areas. Competition between regions is working – if we let it.

Dirk Assmann // Greener pastures

New possibilities in rural areas: digital tools, political decisions and a transparent administration can make the countryside an attractive place bringing together innovation and quality of life.

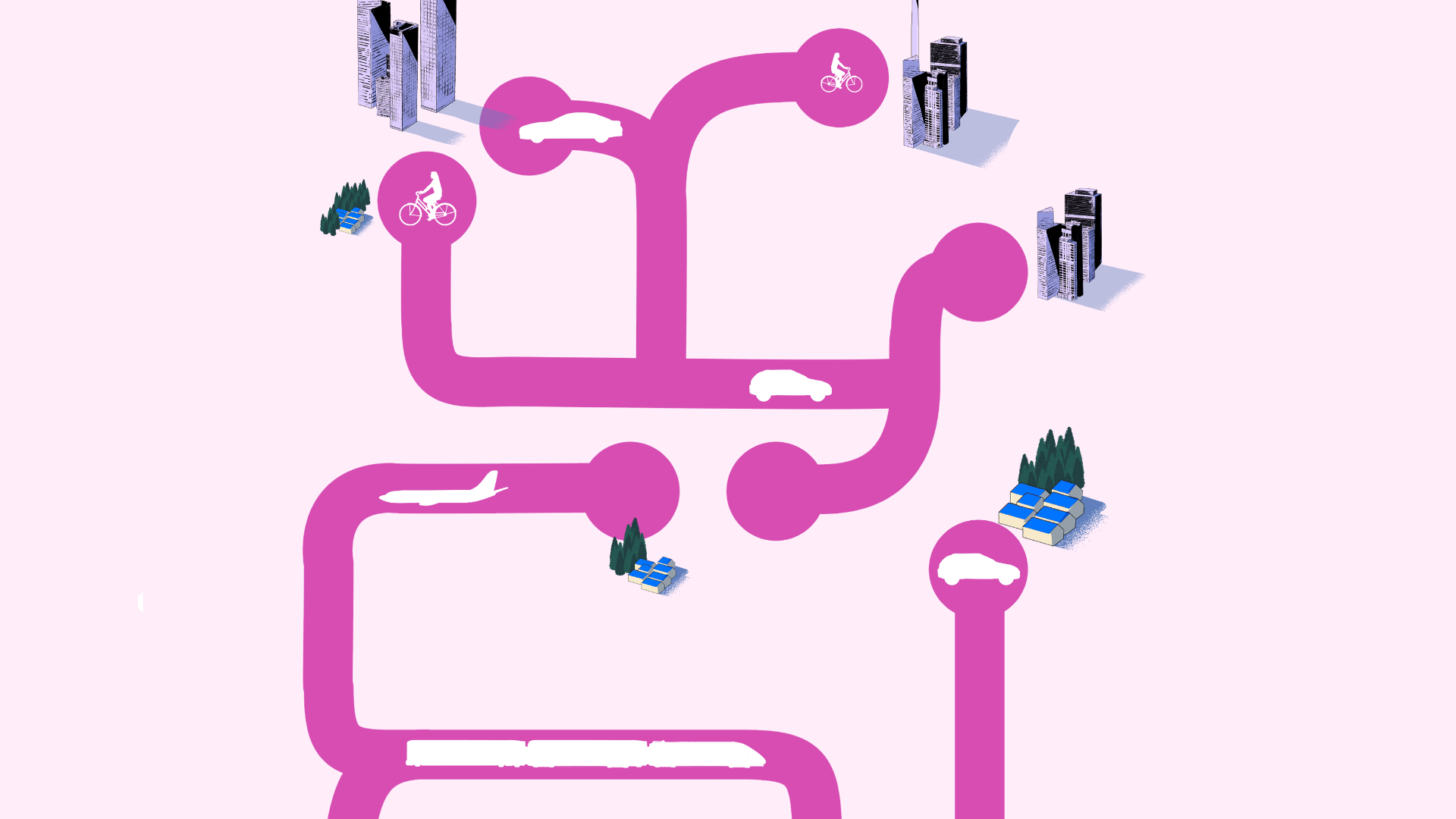

Daniel Zwick // More freedom to move around

When you can zip away to the city at a moment's notice, living in the countryside can be fun. So, expanding the transport infrastructure is really a question of equal opportunity.