DISCONNECTED?

Cities are booming while the countryside is dying?

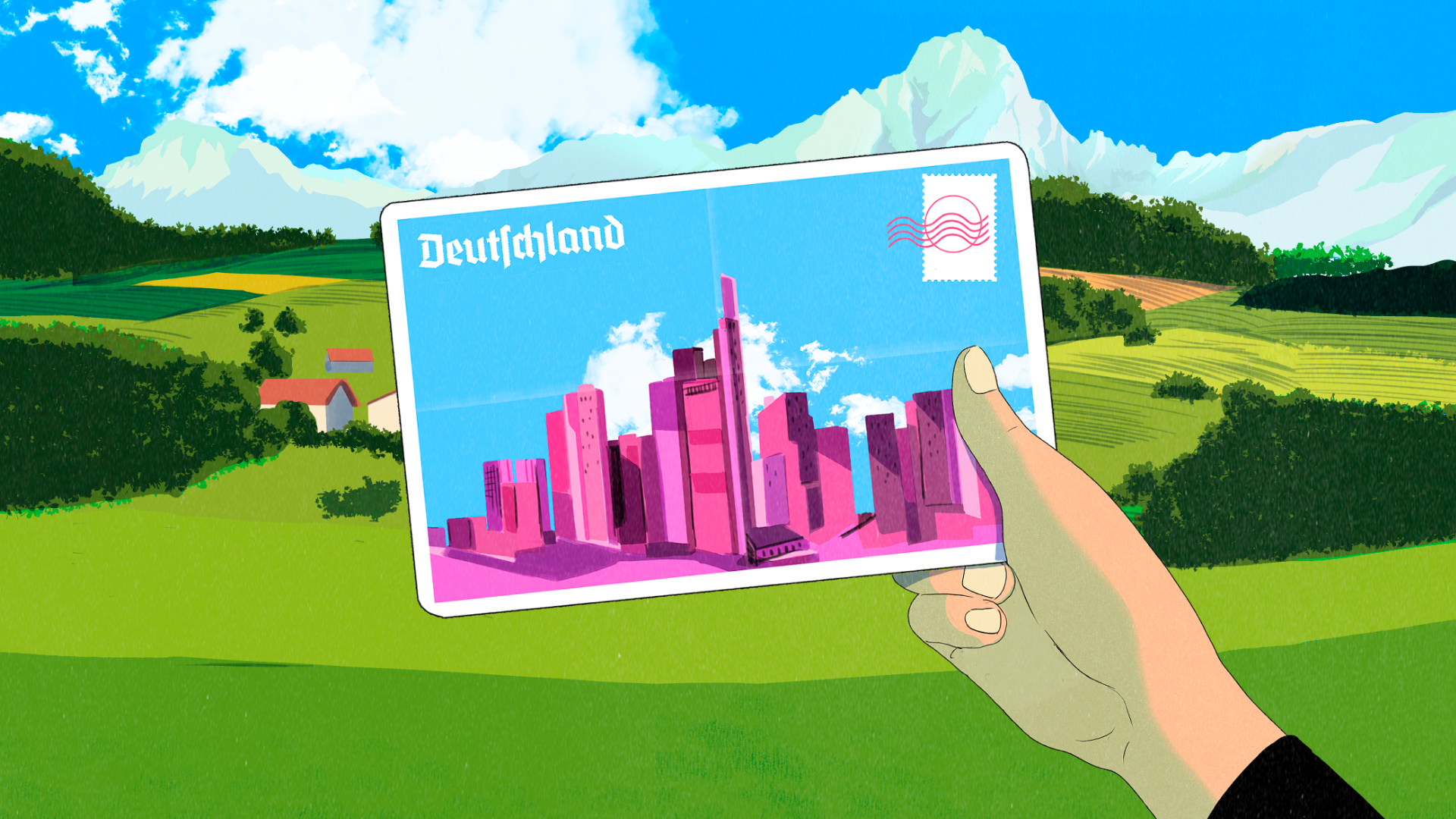

Germany boasts an enviable variety of economic centres in both urban and rural areas. Competition between regions is working – if we let it.

Text: Karl-Heinz Paqué

Illustrations: Emmanuel Polanco

DISCONNECTED?

Cities are booming while the countryside is dying?

Germany boasts an enviable variety of economic centres in both urban and rural areas. Competition between regions is working – if we let it.

Text: Karl-Heinz Paqué

Illustrations: Emmanuel Polanco

The 1990s were a decade of both hope and illusions. In international relations, many saw the fall of the Iron Curtain as a harbinger of a lasting reign of law, democracy and market economy across the globe. At the same time, new technologies and the rise of the internet prompted many economists to predict a golden age of rural areas. And it did make sense. After all, microelectronics and the emerging internet seemed to provide an opportunity to establish wider supply chain networks, giving even remote and sparsely populated regions the chance to partake in the highly productive growth game played in urban metropolises. It seemed to be the beginning of a golden age of the countryside catching up to urban centres.

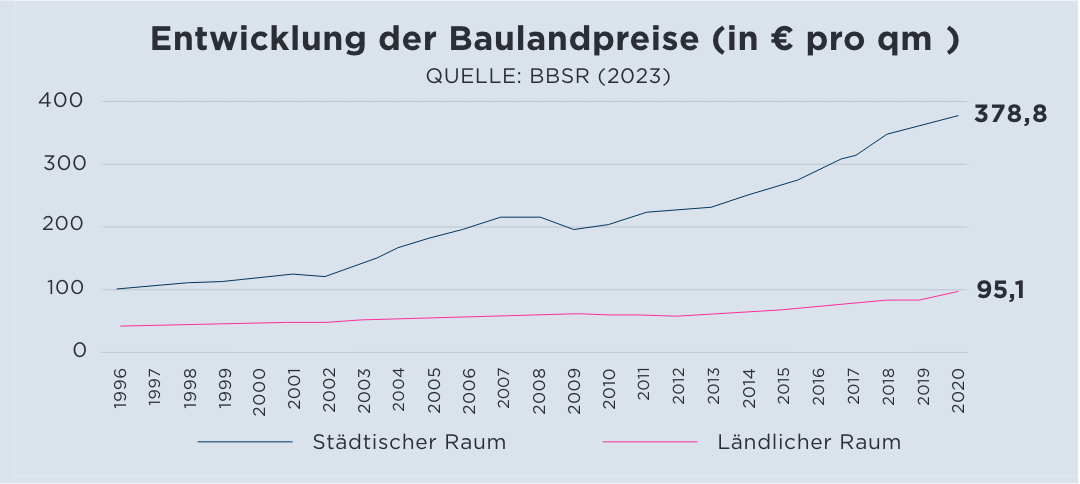

But, as it turned out, history took a different turn. What we have been witnessing in the past 30 years, is cities actually growing a lot faster than rural areas. While the overall population has remained more or less stable, there has been an exodus from the countryside to the city, especially by younger, well-educated people. The most telling sign of this is the trend of residential land prices. According to statistics compiled by Germany's Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR), the residential land price differential between cities and the countryside accelerated from twice as expensive in the 1990s to four times as expensive in 2020; and to the present day, there seems to be a fairly steady uptrend.

That hadn't always been the case. In the decades after WW2 it was mostly the rural areas that benefited from companies relocating and expanding production to small towns, creating an economic boost for the countryside in the process; more and more people getting cars helped, too, of course. Until 1973 Germany had struggled with an extreme labour shortage which resulted in capital concentrating on regions that had at least some qualified labour to offer. More often than not that was rural areas still lagging in their degree of industrialisation. Capital followed labour, not the other way around.

That does not seem to be the case anymore. Which begs the question, why? Well, for one thing, traditional manufacturing was declining in West Germany during the 1970s and 1980s as a result of the oil crises and in eastern Germany during the 1990s as a result of the radical transformation toward a market economy. For another, growth has shifted more and more to the modern service economy which needs highly specialised labour markets typically found in urban centres as well as proximity to related services to realise its full potential. Economists call this “positive regional externalities” that lead to a concentration of economic power.

Which is the exact opposite of what people were hoping for in the 1990s! Is this how it is going to be from here on out? Not necessarily. Two trends suggest otherwise. One, just like more than 50 years ago, we will be experiencing an extreme shortage of labour in the coming years, which will lead to companies being willing to go to even the most remote backwaters to find the last reserves. Two, more importantly, technology will change. Or rather, it has already been changing. Ever bigger and more complex data sets can be sent and received quite easily. So, providing services for the headquarters from a remote branch or home office has become a realistic prospect. Which means that the integration of the corporate centre with the operational periphery might reach a whole new level. “Might” being the operative word, though. It is not a foregone conclusion. After all, it will only be possible if the necessary digital infrastructure is indeed available even in the most remote corners of the country. That requires enormous investment, from both the public and the private sector. Other countries such as Estonia have long since proven that it can be done, though.

Infrastructure and a spirit of innovation

Traffic infrastructure in rural areas remains a political priority that had been neglected during the Merkel era, too. Let's not kid ourselves, even in the digital age will still need modern, fast and reliable transport routes, both road and rail. If rural areas want to stand a chance competing for business with urban hubs they need to be well-connected physically, too.

Regional diversification has its downsides: in boom towns people with low-income jobs struggle with elevated land prices and rents.

And there needs to be a spirit of innovation which emanates from town hall – or it doesn’t. It depends on how much autonomy the local constitution allows. Such a spirit of innovation is indispensable and a function of individuals’ personal initiative. It can be astounding to see how it all works just perfectly in one municipality with commercial zones bursting at the seams, while the neighbouring town is languishing. This is democratic competition that needs to be welcomed.

More generally, we need to accept that not everything can be controlled. Trying to do so against the forces of competition usually doesn't have the desired effect. The German Mietpreisbremse, a rent control mechanism in metropolitan areas, is a case in point. Fundamentally, rising rents – whether we like them or not – are a sign of economic success in a particular region or area. The fact that London, New York and Paris are very expensive cities, is a reflection of their attractiveness as vibrant metropolises, both in their respective countries and on a global level. High land prices and rents in big cities create an incentive for people and companies to look for homes and business locations elsewhere. This way, they contribute to a rebalancing between regions. They reduce the gap in real income and make it so that the cost-benefit ratio is about the same in rural and urban areas. This makes them absolutely indispensable if regions outside the big hubs are to have a chance of getting ahead.

Competition between regions

Germany, with its unique economic history, is a prime example. A patchwork of principalities, the country historically had an abundance of large, medium-sized and small centres that were competing with each other economically and culturally above all. Clearly, that competition didn’t hurt. On the contrary. Precisely because of it, Germany developed the variety that has been the envy of visitors from more centralised nations to this day. And it is that very variety that proves it isn't even desirable to have the same standards of living in urban and rural areas. Often, individuals come to realise at a certain point in their life that their preferences have changed, sometimes even turning wealthy urbanites into downshifters roughing it in the country. That's how the Fläming Heath in Brandenburg came to be flooded with cosmopolitans from Berlin, how the Bavarian Forest came to be teeming with city slickers from Munich and how the Schleswig-Holstein Geest turned into a refuge for Hamburgers – all of them trying to escape the pressures of the big cities.

There is no denying the fact that regional diversification has its downsides. Those who live in boom towns and don't have high-paying jobs struggle with elevated land prices and rents. If you are a low-income nurse in Berlin, Hamburg or Munich and have to pay an exorbitant rent, it won't help you to hear about the importance of competition between economic regions. However, especially when it comes to indispensable services we have to ask ourselves why those jobs don't pay better in big cities. In a social market economy, government sets minimum wage; beyond that it cannot be expected to make sure that vital workers get paid enough so that they can afford their apartments. That has always been and remains the purview of collective bargaining parties.

Karl-Heinz Paqué is Chairman of the Board at the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom and a professor of economics. The gap between urban and rural areas is a topic he has been focussing on since his university studies in the 1970s.

Karl-Heinz Paqué is Chairman of the Board at the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom and a professor of economics. The gap between urban and rural areas is a topic he has been focussing on since his university studies in the 1970s.

Also interesting

Dirk Assmann // Greener pastures

New possibilities in rural areas: digital tools, political decisions and a transparent administration can make the countryside an attractive place bringing together innovation and quality of life.

Daniel Zwick // More freedom to move around

When you can zip away to the city at a moment's notice, living in the countryside can be fun. So, expanding the transport infrastructure is really a question of equal opportunity.

Judy Born // “Social time keeps us healthy in the city”

The city is a loud and hectic place, while in the countryside long distances make everyday life harder. Mazda Adli, psychiatrist and stress researcher, explains how the two environments can benefit from each other.