DISCONNECTED?

More freedom

to move around

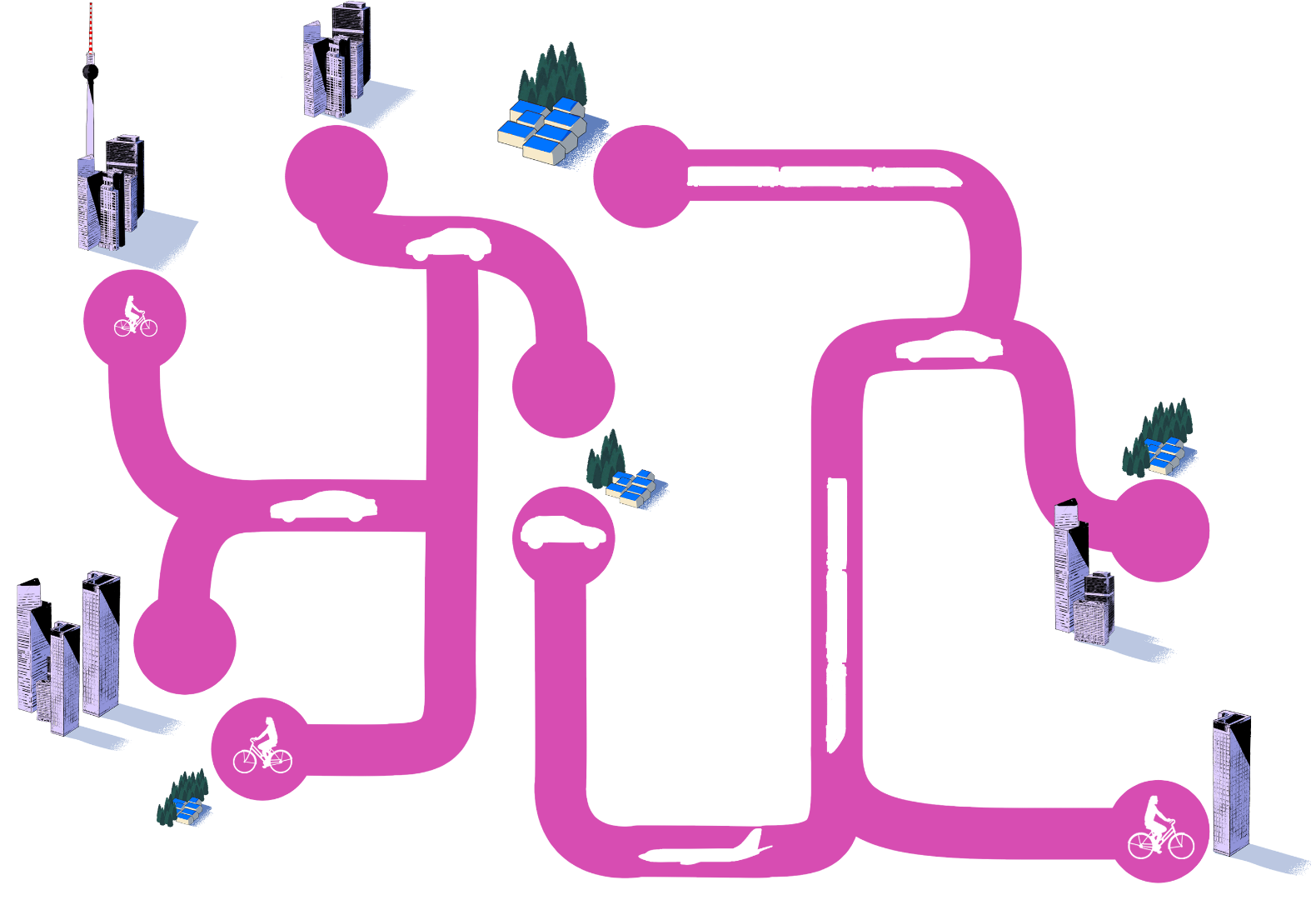

When you can zip away to the city at a moment's notice, living in the countryside can be fun. So, expanding the transport infrastructure is really a question of equal opportunity.

Text: Daniel Zwick

Illustrations: Emmanuel Polanco

DISCONNECTED?

More freedom to move around

When you can zip away to the city at a moment's notice, living in the countryside can be fun. So, expanding the transport infrastructure is really a question of equal opportunity.

Text: Daniel Zwick

Illustrations: Emmanuel Polanco

The Wittenberge train station is a beauty. Dating back to the middle of the 19th century, the classicist building is currently being refurbished and expanded. The small town in Brandenburg's Northwest has big plans for the building: they want to set up a technology centre there and an ophthalmic clinic nearby. It is not so much the architecture but the location that matters. Wittenberge is located right on the railway line from Hamburg to Berlin, pretty much halfway between the two cities. That is what once caused it to become an industrial town. “Without access to the long-distance rail network the city of Wittenberge wouldn't exist in its current form,” says mayor Oliver Hermann, who has a PhD in history. Today, the rail link – or rather the ICE high-speed train, to be precise – is once again turning into a decisive economic factor.

New traffic infrastructure for regions with an ageing population?

Since roads, railway lines and rivers are the bedrock of economic development, local politicians and businesses pretty much always call for better transport links, especially when their region is located far away from big cities. It is about prosperity, justice and the opportunity to lead a good life in the countryside. But priorities have shifted: how well rural areas are connected nowadays depends on how fast commuters can get from here to there. While the costs of transporting goods are an important factor in an export-oriented economy, the bulk of efficiency gains have already been realised there, says Gabriel Ahlfeldt, professor of economics at the London School of Economics. Germany has a very well-developed transport network spanning 229,600 kilometres of roadways outside of cities and towns as well as 400 kilometres of rail lines. “Today, the more relevant factor in Germany is passenger transport”, Ahlfeldt explains. That is especially true of rural areas where the population is ageing and skilled labour is moving away.

Does it even still make sense to build highways and rail lines there? Here's what the government's Federal Transport Infrastructure Plan has to say on the dilemma: “Expanding the infrastructure where it is not expected to make sense from a macroeconomic perspective in the long run due to demographic change” is to be avoided. “At the same time, a basic offer is to be provided even in economically underdeveloped regions with a declining population.” Transport planners respond with a benefit-cost approach, i.e. they determine the relationship between the economic benefits and the social costs of a new transport route, for instance land consumption, noise pollution or CO2 emissions.

Benefit-cost considerations aside, government needs to deal with the question of where its citizens want to live. From this perspective, infrastructure expansion is all about justice. “If transport planning is solely based on demand, you risk losing certain parts of the country. People being forced to leave their home region – something we have been witnessing in eastern Germany for decades – cannot be the solution,” Ahlfeldt says. Instead, he suggests connecting those regions to the next big “centre of growth” in “commutable distance”, for example with a fast rail link.

If transport planning is based solely on demand, you risk losing certain parts of the country.

Such as the one that has just been completed between the cities of Stuttgart and Ulm. With the launch of this high-speed line this past December smaller towns moved closer to the large cities. The new train station in Merklingen, a village located directly on the A8 motorway, is now only 12 minutes away from downtown Ulm; going in the other direction the train reaches Stuttgart in only half an hour. It is connections like these that are a real benefit for rural areas. “With an ICE high-speed train link, even thinly populated areas can benefit from skilled labour who don't live there,” Ahlfeldt explains. Towns such as Limburg or Montabaur with their politically motivated ICE stops on the Frankfurt-Cologne rail line are a case in point. Both towns have benefited economically. Montabaur, for instance, got a commercial zone complete with designer outlet right across from the train station.

Such as the one that has just been completed between the cities of Stuttgart and Ulm. With the launch of this high-speed line this past December smaller towns moved closer to the large cities. The new train station in Merklingen, a village located directly on the A8 motorway, is now only 12 minutes away from downtown Ulm; going in the other direction the train reaches Stuttgart in only half an hour. It is connections like these that are a real benefit for rural areas. “With an ICE high-speed train link, even thinly populated areas can benefit from skilled labour who don't live there,” Ahlfeldt explains. Towns such as Limburg or Montabaur with their politically motivated ICE stops on the Frankfurt-Cologne rail line are a case in point. Both towns have benefited economically. Montabaur, for instance, got a commercial zone complete with designer outlet right across from the train station.

Different economic situation

Of course there were protests against the planned railway line through the Westerwald, albeit less aggressive ones than most recently at Dannenröder forest in the state of Hesse, where activists tried to stop an extension of the autobahn A49. The Green party wants to stop building new motorways altogether, while the liberal Free Democrats (FDP) would like to complete the few missing connections in the German motorway network. According to the Autobahn GmbH the “largest area without motorways in Germany” is around Wittenberge. That is where a segment of the A14 motorway has not been built yet between the cities of Magdeburg and Schwerin. Construction has already begun on a 1.1 kilometre bridge across the Elbe river and a few more stretches of motorway in that area.

Mayor Hermann considers the autobahn a “necessary condition” for growth. There were quite a few companies that came to Wittenberge assuming that the Halle/Leipzig metropolitan area as well as the maritime ports would be accessible much faster in future, he says. “We receive numerous requests by companies looking to come here. But we have become more selective,” Hermann explains. If the water or energy consumption is too high, for instance, then that company wouldn't be good fit for an area bordering on a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

The economic situation has changed, and with it the transport needs. “In the past we needed work, today we need workers.” Politicians now focus on quality of life,” the mayor explains. Highly qualified specialists tend to commute by train instead of car. That also includes local GPs, radiologists and hospital physicians. “Safeguarding those basic functions depends on a long-distance rail line,” says Hermann.

Without access to the long-distance rail network the city of Wittenberge wouldn't exist in its current form.

On the internet, location is irrelevant

He intends to use that rail link more often in future. Once Deutsche Bahn's “Deutschlandtakt” will be operational, trains from Berlin and Hamburg are going to stop in Wittenberge every hour. They could shuttle in workers and patients for the ophthalmic clinic that is planned to be built there. A one-hour train ride in either direction will make Wittenberge part of two metropolitan areas. “Until the early 2000s, Berlin was like a magnet causing many people to move away from here. Today, there is a countertrend: people are getting out of Berlin,” Hermann observes.

The town’s population of currently around 17,000 people is growing again. Not least because of the work-from-home trend. People who no longer need to go to the office every day can live with a longer commute. Alas, the expansion of the local public transport system remains a challenge. On the “last mile” from the train station to people's homes, public transport simply can't be compared to the big cities, Hermann admits. However, Wittenberge is set to get a really fast internet connection soon. This is just as important as roads and railways, seeing as it not only connects mobile workers with their colleagues but also compensates for the lack of shopping opportunities in the countryside. On the internet, location is irrelevant.

Daniel Zwick is a business editor at the „Welt“ and „Welt am Sonntag“ newspapers. He primarily writes about the structural transformation in the automotive industry and about new mobility. In his home town, Berlin, he almost always travels by bike.

Daniel Zwick is a business editor at the „Welt“ and „Welt am Sonntag“ newspapers. He primarily writes about the structural transformation in the automotive industry and about new mobility. In his home town, Berlin, he almost always travels by bike.

Also interesting

Karl-Heinz Paqué // Cities are booming while the countryside is dying?

Germany boasts an enviable variety of economic centres in both urban and rural areas. Competition between regions is working – if we let it.

Dirk Assmann // Greener pastures

New possibilities in rural areas: digital tools, political decisions and a transparent administration can make the countryside an attractive place bringing together innovation and quality of life.

Judy Born // “Social time keeps us healthy in the city”

The city is a loud and hectic place, while in the countryside long distances make everyday life harder. Mazda Adli, psychiatrist and stress researcher, explains how the two environments can benefit from each other.