WAR IN EUROPE

Propaganda and repression

Freedom of opinion is a thing of the past in Russia. State television disseminates disinformation, independent media are harassed.

TEXT: IRINA BOROGAN UND ANDREJ SOLDATOW

WAR IN EUROPE

Propaganda and repression

Freedom of opinion is a thing of the past in Russia. State television disseminates disinformation, independent media are harassed.

TEXT: IRINA BOROGAN UND ANDREJ SOLDATOW

Russia's destruction in Ukraine comes with massive domestic propaganda, disinformation and repression at home. The Kremlin is doing its utmost to keep as many people as possible ignorant of the havoc currently being wreaked under its orders in Ukraine. This prevents a thorough public debate, let alone open protest. Only a few people show the conviction to venture out into the street. Following the invasion in February, only a few courageous souls dared demonstrate against the war in the centre of Moscow. They were all promptly arrested. Since then, the demonstrations have been more frequent and larger, but the authorities are there every time to violently suppress them.

State television has been broadcasting anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western propaganda incessantly, so the Russians have had less and less solid information about their neighbours in the West.

Demonstrations in 2014

It wasn’t like that seven years ago, when Russia annexed Crimea. That was in 2014, when the Russians resembled an angry hornets’ nest. Society was split, initially over the Maidan revolution and then over Crimea. The people engaged in heated debate on Facebook and Twitter. Moreover, the debate at that time was not restricted to the internet and virtual media. On the contrary, in September 2014, tens of thousands of liberal-minded citizens took to the streets in Moscow alone to demonstrate against the war. The liberal media reported extensively on the protests and thus contributed to the debate in society.

Since 2014, however, the Kremlin has been running an extensive propaganda campaign. State television has been broadcasting anti-Ukrainian and anti-Western propaganda incessantly, so the Russians have had less and less solid information about their neighbours in the West. The counter-campaign from abroad, which has emphasised Russia's aggression almost daily, on the other hand, has not been fully received, to say the least. Thus, many Russians have become alienated from Ukrainians. Paralysed by a general sense of fatigue, many citizens have also simply lost interest.

It has become dangerous in Russia to speak out on Ukraine. A case in point is the attack by pro-Kremlin activists on the office of the prestigious Memorial Human Rights Centre in Moscow in October 2021 – during a public event showing a Ukrainian film about the Holodomor, the famine in Ukraine caused by Stalin in the 1930s that killed millions of people. The police arrived. But instead of arresting the thugs, they ended the event. Soon after, Memorial was banned and disbanded.

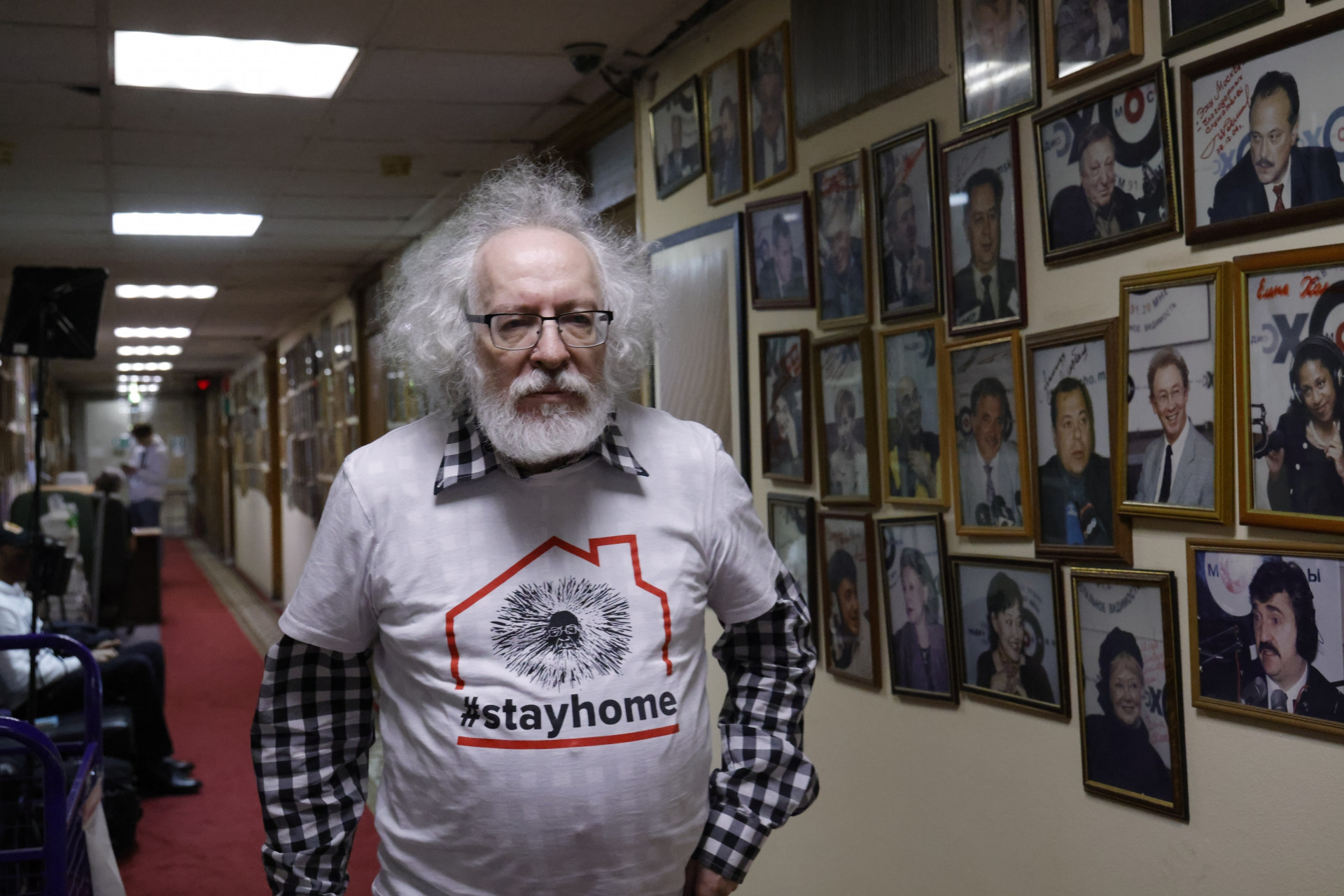

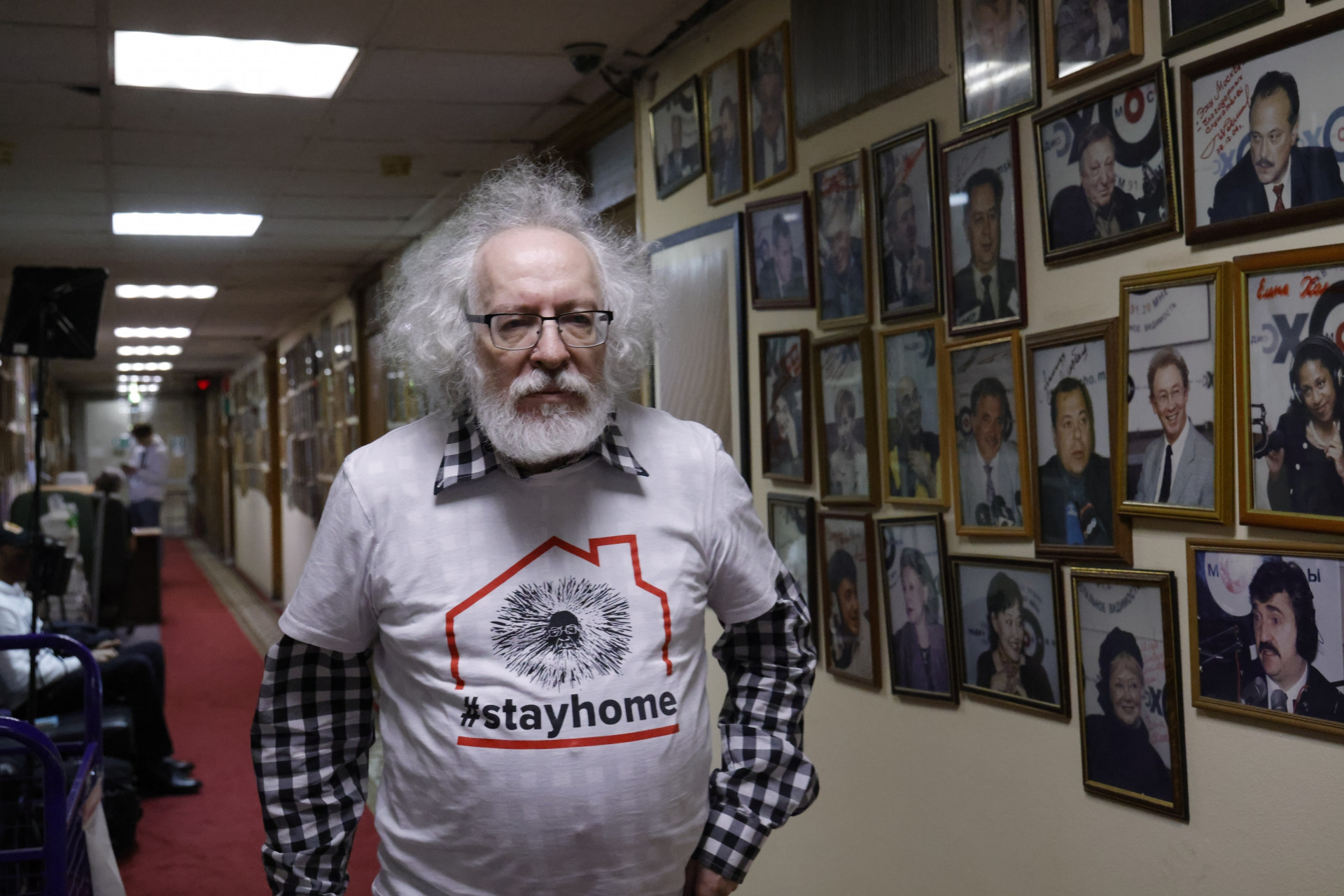

Alexei Venediktov was editor-in-chief of Echo Moskwy, a radio station critical of the Kremlin. In early March the Kremlin had the radio station closed down; the employees were let go.

Alexei Venediktov was editor-in-chief of Echo Moskwy, a radio station critical of the Kremlin. In early March the Kremlin had the radio station closed down; the employees were let go.

Hunt for Ukrainian spies

The fact that the Russian secret service FSB started a hunt for Ukrainian spies in 2014 immediately after the annexation of Crimea did not help many people's sense of security or freedom of expression. Many locals in the occupied territories are too afraid to even talk to journalists. As a result, the Russian public is largely unaware of how, for example, living conditions in Crimea have changed since the annexation. People in eastern Ukraine, which is controlled by pro-Kremlin forces, are also unable to openly criticise the regime that has governed them since 2014.

Social media is no better. VKontakte (VK), the country's most popular social media channel, changed hands in 2014. The reason: its owner at the time refused to pass on personal data of the Maidan demonstrators in Kyiv to the Russian security services. Since then, VK, which is now completely under Kremlin control, has worked closely with the Russian security services and suppressed hundreds of bloggers who had attracted attention by criticising the Kremlin. It has become increasingly dangerous to have a discussion about Ukraine on VK. It has become equally impossible to hear the views of Ukrainians, since the Ukrainian government banned the use of VK in Ukraine in May 2017.

The harassment of the independent press does the rest. In 2014 and 2015, all three liberal Moscow dailies – “Kommersant”, “RBC” and “Vedomosti” – reported extensively on events in Ukraine. That is no longer the case. Since 2014, these media have experienced a constant exodus of journalists due to pressure from the Kremlin, which has also affected their coverage of Ukraine. Today, there is only one newspaper where you can find honest reporting on the events in eastern Ukraine and which is still available in print to Russians: Novaya Gazeta, with a circulation of just about 100,000 copies (in 2015 it was more than 200,000).

Free television reporting has gone the same way. TV Doschd, the only Russian television station critical of the Kremlin, had already been under pressure since January 2014 and was expelled from the country's cable networks shortly afterwards, so that it could only be accessed via the internet. Nevertheless, the station's journalists remained active in Crimea and then in eastern Ukraine. But the work became more difficult because Ukraine banned broadcasts of TV Doschd on the cable network in 2017. Then, in August 2021, the station was classified as a “foreign agent” by Russian censors. On 1 March 2022, after the Russian invasion, it was blocked by the Moscow authorities for its coverage that did not correspond to official propaganda.

There is only one newspaper where you can find honest reporting on the events in eastern Ukraine: Novaya Gazeta, with a circulation of just about 100,000 copies.

More voices go quiet

The ban initially also affected foreign media, including the BBC and Deutsche Welle. Now that alleged “fakes” about the war in Ukraine are punishable by heavy fines or imprisonment, many foreign media are taking the precaution of withdrawing their correspondents. The outcome is that more reliable voices on what is happening in the country have gone quiet: both for foreign countries and the Russians themselves. Online media in Russia have also been under pressure since 2014. In March 2014, three days before the Moscow-staged referendum on the annexation of Crimea, the Russian internet censorship agency Roskomnadzor blocked three independent opposition news media – Kasparov.ru, Ej.ru and Grani.ru. The three blocked websites were popular liberal platforms that provided a forum for intellectuals, journalists and activists critical of the Kremlin. The sites are still blocked.

The most popular online medium in 2014 was Lenta.ru. It was also critical of the Kremlin and reported extensively on the annexation of Crimea. However, it was deleted by its owners in March 2014 on the Kremlin's instructions. Lenta's journalists moved to Riga, where they founded Meduza instead. Meduza remains the most popular online medium in Russian and in Russia. Recently, Meduza was also classified as a “foreign agent” by the Russian authorities. As a result, many employees left the portal. Now Meduza has limited resources to send reporters to Ukraine. Other online media that used to report on what was happening in Ukraine are now limited to publishing short news items and terse commentaries. That is not just to do with the current war: it had already become more difficult for Russian journalists to visit and do research in Ukraine in the past seven years; anyone who had previously been to Crimea was denied entry to Ukraine. But self-censorship also played a role, especially the fear of increasing harassment by the Russian authorities.

Irina Borogan and Andrei Soldatov are Russian investigative journalists and secret service experts. They head the critical news portal Agentura.ru founded in 2000. They most recently published together “The Compatriots: The Brutal and Chaotic History of Russia's Exiles, Émigrés, and Agents Abroad” (Public Affairs, 2019).

Irina Borogan and Andrei Soldatov are Russian investigative journalists and secret service experts. They head the critical news portal Agentura.ru founded in 2000. They most recently published together “The Compatriots: The Brutal and Chaotic History of Russia's Exiles, Émigrés, and Agents Abroad” (Public Affairs, 2019).

More articles

Wolfgang Gerhardt // A danger to the neighbours

Violence is an established component of the Russian box of tricks. But there is no war in which one wins what the other loses. There is just human suffering for everyone.

Josef Joffe // Braving the cold for Kyiv?

All of a sudden, the West remembers Schiller’s observation: “The most pious man can’t stay in peace, if it does not, please his evil neighbour.” There is more than just Ukraine at stake; Europe’s 77-year-old reign of peace, the longest ever, is on the line.

Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger // Putin on trial!

The only way to deal with the brutal and unscrupulous actions of the Russian ruler is to make clear decisions – and to use the full force of national and international justice. That is why Gerhart Baum and Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger have filed charges against Putin.