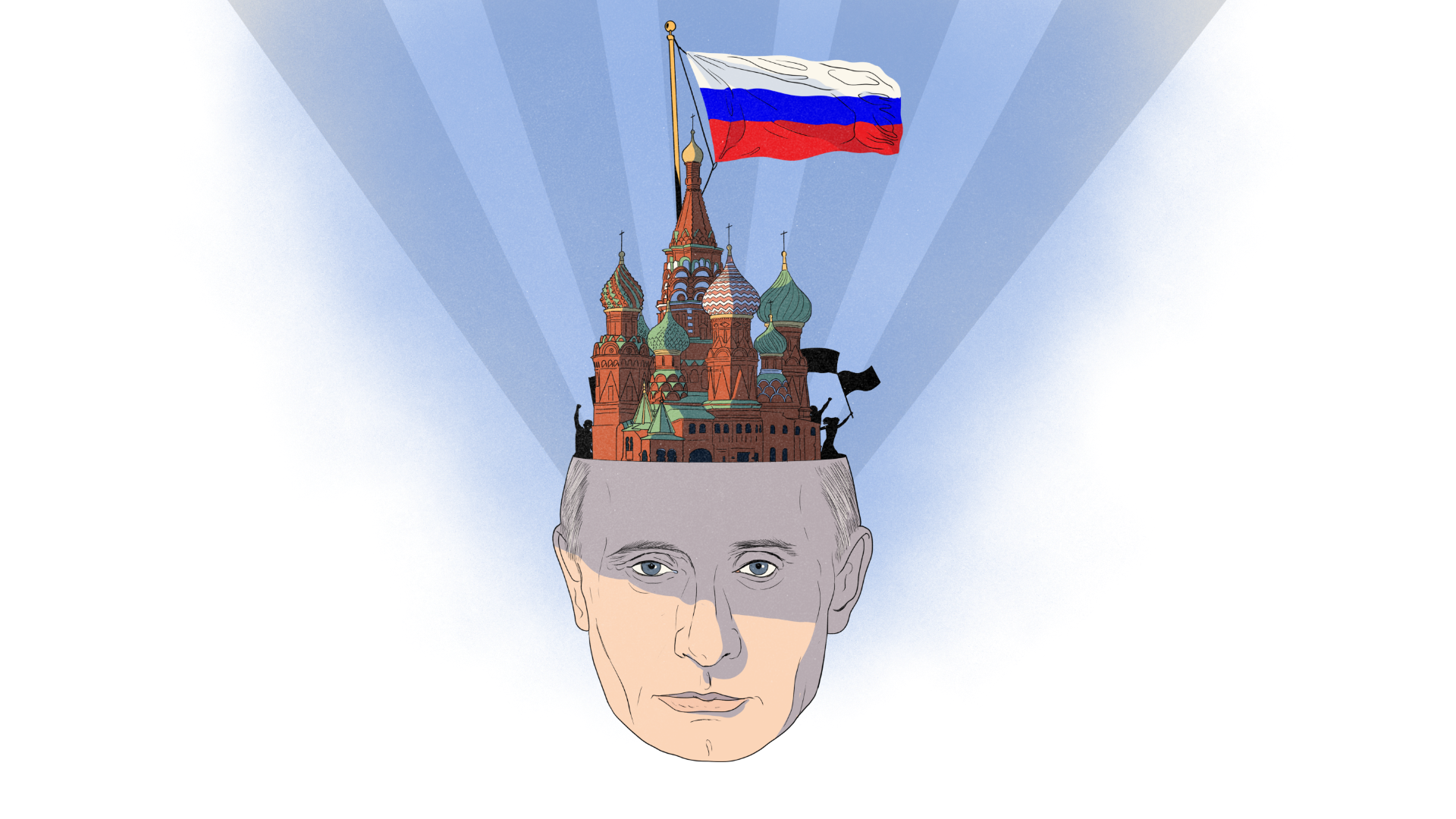

WAR IN EUROPE

“Putin‘s ideology is the sacralisation of war“

The horrific actions of the Russian ruler appear on the news every day. And his comments are bewildering. What on earth is going on in the head of the former KGB spy in the Kremlin? Philosopher Michel Eltchaninoff has researched the origins of the Putin school of thought and the ideology he has formed.

TEXT: KAREN HORN

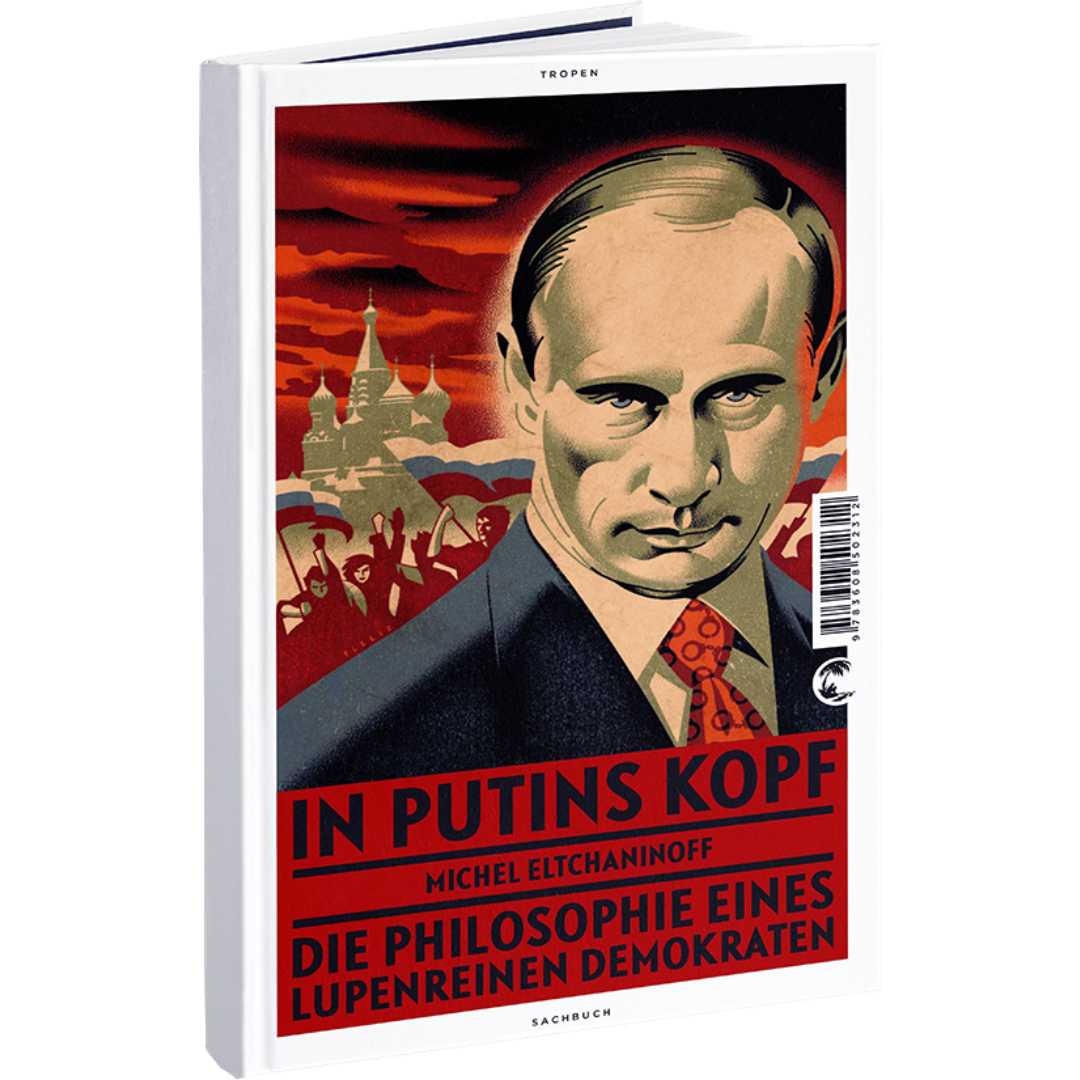

ILLUSTRATION: EMMANUEL POLANCO/SEPIA

WAR IN EUROPE

“Putin‘s ideology is the sacralisation of war“

The horrific actions of the Russian ruler appear on the news every day. And his comments are bewildering. What on earth is going on in the head of the former KGB spy in the Kremlin? Philosopher Michel Eltchaninoff has researched the origins of the Putin school of thought and the ideology he has formed.

TEXT: KAREN HORN

ILLUSTRATION: EMMANUEL POLANCO/SEPIA

Why has the Russian ruler Vladimir Putin decided to attack Ukraine now and make impossible demands on the West, especially NATO?

In the 2018 elections, Putin promised a “Russia for the people“: that was his slogan. In the almost four years since, however, he has done little. He has changed the constitution so he can remain in office until 2036; he has made some highly unpopular reforms to the pension system; he has poisoned and imprisoned his critic and competitor Alexej Navalny. But he has not managed to initiate a political movement to his benefit. His popularity is eroding perceptibly.

Does that even matter to him? Is he interested in public opinion at all?

The Kremlin does not need the people. Putin does not have to ask anyone’s permission. However, his strength does stem from his appeal to the people, his ability to win them over and mobilise them. That legitimises his actions. This appeal is now weaker than it was in 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea. The people have grown as tired of the propaganda and threats of war as they are of corruption and the difficult economic situation. He had to do something with a view to the 2024 elections. That’s why he is trying, with the support of state media, to whip up nationalistic frenzy and foment Russian nationalism into a siege mentality.

Does Putin not predominantly have geopolitical ambitions that are an end in themselves?

Yes, of course. During Donald Trump’s term in the White House, Putin came to the realisation that he must bring Russia back into the mix in the power play between the US and China. And since Joe Biden began his term, a person as despised in the Kremlin as all other Democratic US presidents, he seems to believe now is the right time. However, it is important to remember that Putin thinks long term. He has been President since 2000 and can remain in office until 2036.

What does Putin want?

Following what was widely perceived as the traumatic humiliation of the collapse of the Soviet empire, Putin is doing everything he can to prevent the continued fragmentation of Russia and to reverse the trend through new territorial expansion. In doing so, he follows the thinker Lev Gumilyov in the pseudo-scientific idea that every nation has its own life energy, and that Russia's superior nature as a young, new country filled with cosmic power calls for continued expansion.

Excuse me?

The Tsars expanded Russian territory step by step. The Soviet Union adopted the same approach; it is not for nothing that the conquest of space happened during the Soviet era. That is real and deeply symbolic at the same time: the Russian reaching for the stars. There has been a messianism in Russian culture since at least the 16th century. Russia thus considers itself entrusted with a universal civilising mission at certain moments in its history.

Do the Russians relate to that?

It may not reflect public opinion, but it does touch on something deep within the Russian culture. They have this dangerous idea that they are really special and therefore entitled to show or prove something to the world. It’s no coincidence that Russia turned into the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union was an idea, a concept.

And the West stands in the way of his imperialism.

Yes, the West of all places, which is old, tired and drained according to Gumilyov’s theory, i.e. its life energy is on the wane. Putin is constantly spreading the narrative of the outrage of Russia being pushed into a corner and kept down. He says the West wanted to prevent Russia from regaining the greatness that belonged to the nation by right.

Presenting Russia as the victim?

Yes, exactly that.

Are we talking about a return to Tsardom or to the Soviet Union?

Neither. Nevertheless, Putin’s foreign policy is reminiscent of the Tsars and Stalin. It’s all driven by this paranoia that goes back to his KGB training.

Can Putin’s school of thought be seen as a coherent ideology?

No. Putin understands how intellectually disoriented the Russian people have been since the fall of the Soviet Union. The people had lived with Marxism-Leninism for 70 years. And even if they didn’t believe in it, they were still shaped by this ideology, as was Putin himself. Putin is now offering them a new ideological narrative that gives them stability. Putinism plays on various sensitivities that are meaningful in Russia, for example when he identifies with Orthodox Christianity, which was largely suppressed during the Soviet era, with Russian ethnicity, the sublime Slavic soul, or Eurasianism, according to which Russia should turn towards Asia.

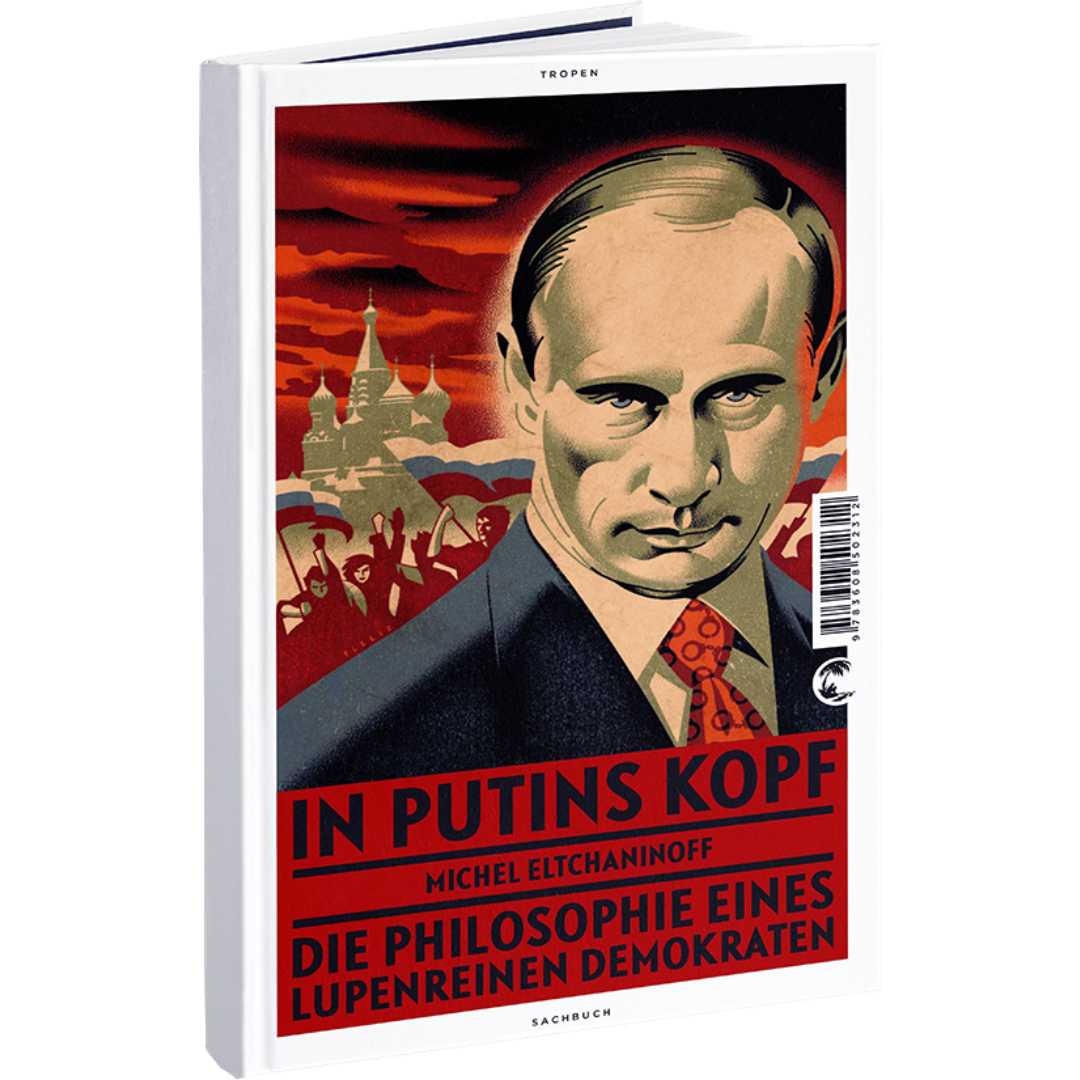

The essay “Dans la tête de Vladimir Poutine” by Michel Eltchaninoff was published in 2015. The English translation “Inside the Mind of Vladimir Putin” was published in 2018.

The essay “Dans la tête de Vladimir Poutine” by Michel Eltchaninoff was published in 2015. The English translation “Inside the Mind of Vladimir Putin” was published in 2018.

But how does it all fit together?

Essential components of this Putinism are conservatism, anti-Americanism and the rejection of all political correctness. The common thread in this patchwork is hatred of the decadent West, imperialism and readiness for war. However, Putin wants to use this message not only to bring his own people on board, but to win over the whole world. This export mentality, so to speak, distinguishes this ideology from the doctrines of other authoritarian states like China or Iran.

But what is supposed to be so attractive about this message?

Spirituality. The Russians have a strong idealistic streak. As Putin sees it, they have a religious, compassionate soul and are ready to die. “In Russia, even death is still beautiful,” says a proverb that Putin likes to quote. In his view, we in the rich West are materialists, we only care about our comfort. We know no patriotism, no willingness to sacrifice, we don’t fight for anything.

In your book “Inside the Mind of Vladimir Putin” you also refer to the sometimes quite bizarre glorification of the military in Russia. Is that also connected to this ideology?

Putin‘s ideology is a sacralisation of war. We have been observing a militarisation of Russian society for several years. Children receive a basic patriotic education in school and learn how to handle weapons. And the military is celebrated. Just look at the Central Armed Forces Museum in Moscow, a cathedral to the military adorned with frescoes and mosaics, with tanks and planes on display, or at the March of the Immortal Regiment every 9 May. Every family is urged to join the march and carry photos of ancestors who died in the war in front of them. In addition, there is the collective memory of the Second World War. The people are proud of their victory.

But should that not build a bridge to the West? After all, the Russians did not achieve victory over Hitler's Germany by themselves.

Putin entirely ignores the involvement of the Western allies. And he expects gratitude from the West for the Soviet soldiers having defeated National Socialism. As he doesn't get it the way he wants, his thoughts turn to revenge.

How important is Putin himself in all this? Could the Kremlin advocate Putinism without him?

It’s hard to imagine Russia without Putin these days. However, there are of course possible successors in his entourage, and the danger is that these people will think like he does. Take Sergei Schoigu, for example.

… the so-called defence minister, i.e. leader of the Russian armed forces.

Yes. Only the Russians themselves can really answer whether Putinism can exist without Putin. He may have already set the course institutionally, economically and mentally. He may also already have succeeded in convincing people that the idea matters more than the reality. There may, however, also be an awakening, by the time he has gone, if not before, when people understand that his ideology was a mere illusion and that their country lost more than it gained under him and his ideology.

Michel Eltchaninoff is editor-in-chief of “Philosophie Magazine”, the French counterpart of the German “Philosophie Magazin”. His academic specialisation is Russian philosophy.

Michel Eltchaninoff is editor-in-chief of “Philosophie Magazine”, the French counterpart of the German “Philosophie Magazin”. His academic specialisation is Russian philosophy.

More articles

Wolfram Eilenberger // Russia’s work and Germany’s contribution

Putin‘s invasion of Ukraine has shaken German politics out of its naivety. How could the country so collectively succumb to such a dangerous misconception?

Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger // Putin on trial!

The only way to deal with the brutal and unscrupulous actions of the Russian ruler is to make clear decisions – and to use the full force of national and international justice. That is why Gerhart Baum and Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger have filed charges against Putin.

Karl-Heinz Paqué // A course correction for Germany

We need more investment in defence and a sensible energy transition. We also need a growth-oriented economic policy to finance it.